Active transport is the process by which cells move molecules against their concentration gradient, from a region of low concentration to high concentration, using energy (ATP).

This is essential for maintaining proper cell function, especially in nerve and muscle cells, and for nutrient absorption.

Active transport is an energy-driven process where membrane proteins transport molecules across cells, mainly classified as primary or secondary, based on how energy is coupled to fuel these mechanisms. The former constitutes the means by which a chemical reaction, e.g., ATP hydrolysis, powers the direct transport of molecules to establish specific concentration gradients, as seen with sodium/potassium-ATPase and hydrogen-ATPase pumps.

The latter employs those established gradients to transport other molecules. These gradients support the roles of other membrane proteins and other workings of the cell and are crucial to maintaining cellular and bodily homeostasis.

As such, the importance of active transport is apparent when considering the various defects throughout the body that can manifest in a wide variety of diseases, including cystic fibrosis and cholera, all because of an impairment in some aspect of active transport.

⚙️ Steps Involved in Active Transport

1. Recognition of the Substance

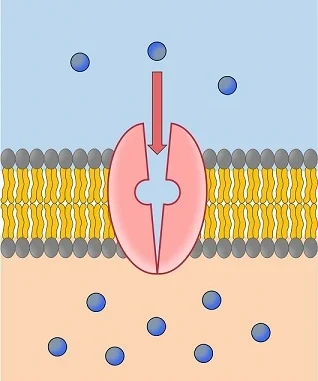

Specific carrier proteins in the cell membrane recognize and bind to the molecule (e.g., ions, glucose, amino acids) that needs to be transported.

2. Binding of the Molecule

The molecule binds to a receptor site on the carrier protein.

The protein is specific — it only binds to certain substances (like a lock and key).

3. Energy Input (ATP)

The carrier protein uses energy from ATP.

ATP is hydrolyzed (broken down) into ADP + phosphate, releasing energy.

This energy changes the shape of the protein (called a conformational change).

4. Transport Across the Membrane

The conformational change in the protein allows the molecule to move across the membrane to the other side (from low to high concentration).

5. Release and Reset

The molecule is released into the cell (or out of the cell, depending on direction).

The carrier protein returns to its original shape, ready to transport another molecule.

🔋 Key Features of Active Transport

Requires energy (ATP)

Works against concentration gradients

Involves specific carrier proteins

Selective and regulated process

📌 Examples of Active Transport

Sodium-Potassium Pump (Na⁺/K⁺ pump): Pumps 3 Na⁺ ions out of the cell and 2 K⁺ ions into the cell.

Calcium ion transport: Important in muscle contraction and neurotransmission.

Glucose transport in intestines (with sodium ions, via co-transport).

Clinical Significance

A highly illustrative example of the importance of active transport is the use of cardiac glycosides like digoxin, which inhibit sodium-potassium ATPase in cardiac cells. Employing primary active transport, this protein normally acts to extrude sodium out of myocytes in exchange for potassium into the cells. In the presence of cardiac glycoside, the intracellular sodium will be higher.

This indirectly inhibits the sodium-calcium exchanger, which normally brings sodium into the cell in exchange for calcium leaving. As such, more calcium is unable to leave the cell, so more calcium can act intracellularly to stimulate cardiac contractility or positive inotropy, implicating its usage in diseases that have decreased inotropy like heart failure. Because potassium is kept in the extracellular space, it can build up and cause hyperkalemia.